Picking up where I left off in the last edition…Researchers who have attempted to predict success in a myriad of responsibilities, are finding that resilience and character may be much more important than more commonly used measures, such as IQ, test scores, and pedigree.

Angela Lee Duckworth, PhD, conducted a series of studies on a concept called "grit." Grit is another word for backbone, chutzpah, fortitude, guts, stick-to-it-iveness, etc. It all started when Dr. Duckworth (while a student in Graduate School) observed that it wasn't necessarily the smartest people who succeeded and made a lasting impact on science.

She had a hunch that it was a person's personal "grit" recipe that made the difference in their level of success. Across six studies, Duckworth found that grit significantly contributed to successful outcomes: Undergrads with the most grit earned higher grade point averages than their peers. West Point Cadets with the highest levels of grit were more likely to return after the first summer. Even "grittier" spelling bee competitors (a situation where IQ would seem the best predictor) out-spelled their less tenacious competitors. Among older individuals, people with substantial grit had higher levels of education and made fewer career changes than less gritty peers of the same age.

In reviewing the literature, there appears to be little explanation as to how a person can acquire grit. So, is this something we either have…or we don't? Is it based on our genetic make-up? Or, are there outside influences that haven't been explored as of yet (socio-economic status, traumatic circumstances early in life, family dynamics, etc..)?

In reviewing the literature, there appears to be little explanation as to how a person can acquire grit. So, is this something we either have…or we don't? Is it based on our genetic make-up? Or, are there outside influences that haven't been explored as of yet (socio-economic status, traumatic circumstances early in life, family dynamics, etc..)?

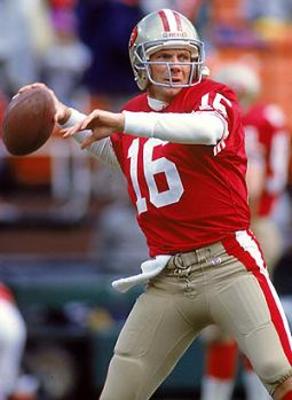

To further reinforce our collective ignorance regarding what genuinely predicts success, we'll look to an article by Bridget Murray titled, “Why We Don't Pick Good Quarterbacks." The article highlights viewpoints by best-selling author, Malcolm Gladwell, who also writes for The New Yorker. Gladwell illustrates the natural biases the NFL continues to display in their stubborn adherence to assessing potential, despite the fact that they are playing a lottery game. To illustrate natural bias and its consequences, Gladwell points to what he calls "the quarterback problem:"

"Each year, the National Football League (NFL) selects new recruits by testing college players physically and cognitively. The tests work fine for most player positions, but when it comes to quarterbacks, said Gladwell, 'they do an absolutely terrible job of predicting who will do well.' Why? Largely because NFL leaders succumb to the natural bias, favoring quarterback candidates who are tall, fast and strong, rather than those who are slower or shorter, 'and who have had to compensate for those deficiencies with increased hard work, guile and intelligence.'

Meanwhile, said Gladwell, the evidence suggests that, if anything, the latter group proves to be better quarterbacks. 'It's about a particular cultural fascination with the idea of potential,' he explained. 'NFL teams think that these [natural athletes] have more room to improve than anybody else.'

Gladwell pointed to Enron as another real-world case study. The company cherry-picked its executives from the nation's top MBA programs and promoted people based on smarts, rather than experience. The result was the worst corporate meltdown in national history…

'Once we've discovered these things that are under our unconscious' control, are we supposed to just stand idly by? No. We should fight the unconscious,' said Gladwell. 'And let's not just do it with theory. Let's do it with corporate America, let's do it with college admissions, and let's do it on the football field….We have in this country a very powerful ideology–or more like mythology–that if you work hard, you will get ahead. Part of what we need to do is to take that mythology–which has been neglected–and refurbish it…And structure our social institutions so that they reflect that.' "

If the above doesn't get you rethinking your own tightly held biases that just might favor style and potential over substance, hard work, grit and other unseen variables, then don't miss the new critically acclaimed movie, "Moneyball." It will surely leave you feeling that what you know just might be limiting your imagination.

What biases do you bring to the table? Write them down, so at least you can be aware of how many candidates you may be prematurely dismissing.

What would happen if you held yourself accountable to put every bias aside and simply ask candidates questions like:

- At what point in your life did you know that you could persevere through any difficulty?

- When did you realize that you had the ability to over-achieve and compete with, apparently, more capable people?

Who knows what gems you'll find in places that you've never looked before…

Editor's Note: This article was written by Dr. David Mashburn. Dave is a Clinical and Consulting Psychologist, a Partner at Tidemark, Inc. and a regular contributor to WorkPuzzle. Comments or questions are welcome. If you're an email subscriber, reply to this WorkPuzzle email. If you read the blog directly from the web, you can click the "comments" link below.