One of the purposes of WorkPuzzle is to facilitate a dialog concerning what makes people flourish in their work. Typically, we address this topic from a scientific perspective.

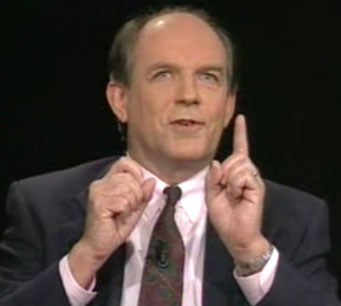

Last week, I ran across the transcript of a speech given by Dr. Charles Murray at the 2009 Irving Kristol Lecture in Washington DC. Dr. Murray is a social scientist and author who is most famously known for his controversial book, The Bell Curve (1994),that discusses the role of intelligence (IQ) in American Culture.

Last week, I ran across the transcript of a speech given by Dr. Charles Murray at the 2009 Irving Kristol Lecture in Washington DC. Dr. Murray is a social scientist and author who is most famously known for his controversial book, The Bell Curve (1994),that discusses the role of intelligence (IQ) in American Culture.

Recently, Dr. Murray has been studying happiness. He approaches the topic from a government/public policy perspective, and much of what he says is probably beyond the interest of the general public. You’re welcome to read the whole speech, but I thought it would be helpful to highlight a couple of passages that would liven our WorkPuzzle discussion.

1. Dr. Murray does a great job of defining happiness:

And since happiness is a word that gets thrown around too casually, the phrase I’ll use from now on is “deep satisfactions.” I’m talking about the kinds of things that we look back upon when we reach old age and let us decide that we can be proud of who we have been and what we have done. Or not.

To become a source of deep satisfaction, a human activity has to meet some stringent requirements. It has to have been important (we don’t get deep satisfaction from trivial things). You have to have put a lot of effort into it (hence the cliché “nothing worth having comes easily”). And you have to have been responsible for the consequences.”

2. Dr. Murray identifies the arenas in life where happiness are derived:

Let me put it formally: If we ask what are the institutions through which human beings achieve deep satisfactions in life, the answer is that there are just four: family, community, vocation, and faith. Two clarifications: “Community” can embrace people who are scattered geographically. “Vocation” can include avocations or causes.

It is not necessary for any individual to make use of all four institutions, nor do I array them in a hierarchy. I merely assert that these four are all there are. The stuff of life–the elemental events surrounding birth, death, raising children, fulfilling one’s personal potential, dealing with adversity, intimate relationships–coping with life as it exists around us in all its richness–occurs within those four institutions.”

If you have the responsibility of coaching someone, these definitions can be very helpful in coming to a common understanding concerning the nature of happiness in a person’s life. It is also useful to have a framework for positioning work (vocation) among the other significant areas from which happiness can be derived.