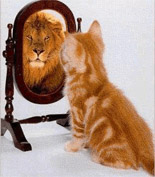

One of our most popular blogs was written around the concept of Coaching for Confidence. Below, are some of the original findings regarding this fascinating subject, along with some additional findings that help improve our understanding of the topic.

It’s no secret that managing and coaching those around us can feel futile if those being coached lack confidence in their ability to succeed. We’ve all witnessed talented people lose their spark and confidence, begin to wilt, and eventually begin to drop below performance standards.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter, an expert on the subject of confidence explains:

“Confidence consists of positive expectations for favorable outcomes. Confidence influences the willingness to invest – to commit money, time, reputation, emotional energy, or other resources – or to withhold or hedge investment. This investment, or its absence, shapes the ability to perform. In that sense, confidence lies at the heart of civilization. Everything about an economy, a society, an organization, or a team depend on it. Every step we take, every investment we make, is based on whether we feel we can count on ourselves and others to accomplish what has been promised. Confidence determines whether our steps – individually or collectivity – are tiny and tentative or big and bold.” (Confidence: Leadership and the Psychology of Turnarounds, 2004)

Recruiting people is just the first stage of an ongoing process. It’s your job as a coach, manager, and/or mentor, to bring out the best in others, which begins with assessing their confidence. They must believe that they can succeed in order to succeed.

Carol Craig at the Centre for Confidence and Well-Being claims that she and her colleagues have developed a formula for confidence. It appears to be quite accurate, with a great deal of research to back it up. It goes like this:

Confidence = Self-efficacy (the belief you can reach your goals) + Optimism.

So what do these terms mean?

Self-efficacy:

“Self-efficacy is the term that psychologists use to describe the belief a person has that they can reach their goals. Unlike self-esteem which is more of a global judgment on the self and its worth, self-efficacy specifically isolates the way an individual assesses their competence in relation to achievements, goals and life events. Self-efficacy expert, Albert Bandura from Stanford University argues that ‘ordinary realities are strewn with impediments, adversities, setbacks, frustrations and inequities.’ He therefore claims that people need ‘a robust sense of efficacy’ to keep trying.”

Research on self-esteem suggests that parents (through genes and parenting style) have the biggest influence on a young person’s self-esteem. However, Bandura and others argue that schools (perhaps even real estate coaching and training…) play a huge role in developing young peoples’ feelings of self-efficacy.

Optimism:

“In everyday life we usually use the word optimism to mean feeling positive about life. Often we refer to someone who is optimistic as seeing ‘the glass as half-full, rather than half-empty.’

In psychology, there are two main ways to define optimism. Scheier and Carver, the authors of the popular optimism measure – The Life Orientation Test – for example, define optimism as ‘the global generalized tendency to believe that one will generally experience good versus bad outcomes in life.’ In everyday language this means ‘looking on the bright side of life.’ In such a definition, pessimism is the tendency to believe ‘if something can go wrong for me, it will.’ The other main way to define optimism is to use the concept of ‘explanatory style.’ This is the approach taken by Professor Martin Seligman, author of Learned Optimism and co-author of The Optimistic Child. He argues that each of us has our own ‘explanatory style,’ a way of thinking about the causes of things that happen in our lives. Optimists are those who see adversities as temporary and restricted to one domain of life while pessimists often see problems as permanent and pervasive.” (Carol Craig, Centre for Confidence and Well-being, 2006).

So, what can you do if those you coach lack confidence? Here are some ideas:

1. Ask them: “Do you believe that you will succeed?” If they don’t, or if they say yes in a tentative manner:

2. Then ask them what they believe the outcome will be if they don’t really believe they can achieve their goals? (Even though my graduate courses were over 23 years ago, I can tell you that those who believed they’d finish and do well, did! Those who didn’t have that confidence, failed!)

3. Once you have them talking about their uncertainty and its impact on their performance: Ask them to remember a time when they did succeed – big time! Urge them to remember their attitude going into the situation. What was their level of confidence? Did they expect success? Why?

4. And lastly, remind them that their best confidence will develop as they focus on developing their strengths, and contributing to clients, co-workers and society at large, rather than taking on important tasks and projects only to bolster their ego. Only under these conditions can one sustain great performance. Because when things don’t go well, it’s not about your ego, it’s about your contribution!

Editor’s Note: This article was written by Dr. David Mashburn. Dave is a Clinical and Consulting Psychologist, Partner at Tidemark, Inc. and a regular contributor to WorkPuzzle. Comments or questions are welcome. If you’re an email subscriber, reply to this WorkPuzzle email. If you read the blog directly from the web, you can click the “comments” link below.